Public Domain

Former USAF F-105 pilot Skip Holm provided the following first-hand experiencing flying the 'Thud' in Southeast Asia during the Vietnam War.

Thud Thai: Flying Low, Fast & Deadly

Skip Holm Remembers Flying the F-105

By: Mark Huber

Republic F-105 Thunderchiefs flew more combat missions over North Vietnam than any other aircraft. Almost 60 percent of the 600 “Thud” fighter-bombers flown in the Vietnam War were lost. Not since B-17s flew unescorted against World War II Germany had American aviators been caught in this kind of carnage.

Skip Holm flew 105s in Southeast Asia and survived.

Holm is a thin and plain spoken North Dakotan. His mischievous smile is fueled by a passion for pranks. He is the misbehaving cartoon kid Dennis the Menace in a flight suit.

Holm holds the record for most combat hours flown by any fighter pilot in the U.S. Air Force; 1,171. All were during Vietnam and almost half were in F-105s. At 60, he remains one of the world’s foremost test pilots. He also is champion air racer, air show performer, and movie stunt pilot. During three tours in Southeast Asia he won three Distinguished Flying Crosses, 25 Air Medals, and numerous commendations. Flying 163 missions in 1968 and 1969 from bases in Korat and Takhli, Thailand, Holm logged 471 combat hours in F-105s. (The rest of his combat time would come later in the war flying F-4s.) The Thud is one of his favorite fighters out of the dozens he has flown.

Calling the Thud a fighter is really a misnomer. It was big: It stood twenty feet tall and fully loaded weighed 40,000 pounds. One could walk under the wing without stooping. If a pilot tried to get out of the cockpit without a ladder he was going to break bones.

While it was equipped with a 20 millimeter Gattling canon and air-to-air missiles, the Thud was an undistinguished dogfighter. There was no rearward visibility from the cockpit. Its high speeds and small, 45 degree swept wings gave it a huge turning radius.

In combat, pilots were told to engage the enemy head-on or outrun him. Because of its high stall speed, the minimum airspeed required for the wings to produce lift, takeoffs and landings in Thuds were never routine. With a full 6,000-pound bomb load, Thuds didn’t lift off until they hit 250 knots, 288 miles-per-hour, and easily used almost 9,000 feet of runway to get airborne.

Engaging the fuel-sucking, flame-spitting afterburner wasn’t something you did occasionally in a Thud for momentary extra power, like it is in most other fighters: It was a way of life.

Built by Republic Aircraft on Long Island, the single-engine F-105 was designed in 1951 during the Cold War. Mission: Take off from NATO bases and fly low and fast, 200 feet and 800 knots, and drop a tactical nuclear weapon on a member of the Warsaw Pact. By the early 1960s, it was a task rendered largely obsolete by ballistic nuclear missiles. However, a new mission for Thuds awaited in Vietnam.

Holm began his 105 training at McConnell AFB, Kansas in November 1967 under the tutelage of the notorious squadron commander, Lt. Col. Jim “Black Matt” Matthews. Black Matt had flown as a member of the Air Force’s demonstration team, the Thunderbirds. He is better known for making a supersonic pass in a 105 over U.S. Air Force Academy on May 31, 1968, breaking more than 300 large dorm and dining hall windows.

Holm was an impressionable second lieutenant. To this day he calls Matt one of his personal heroes.

Public Domain

Matt prepared the squadron for battle with a militarized version of fraternity hazing coupled with old salt combat wisdom. As training ended in May 1968, Holm flew a simulated combat sortie with a gaggle of 37 other airplanes from Thailand to Hanoi, using the route between McConnell and George Air Force Base in California. In route, F-100s pretended to be attacking MiGs and mock anti-aircraft artillery (triple A) fire shot up from Western slopes of the Colorado Rockies.

The “target” was in the desert on the California-Nevada border. Senior squadron leaders led the strike that dropped live bombs. The phone began to ring at George. They had bombed the Last Chance gas station by mistake.

Actually, they bombed near it. They were aiming for it, but missed.

In retrospect, Holm realized this was a perfect primer for Vietnam. “You had a bunch of airplanes flying against one target, and you missed.” He was on his way to Thailand.

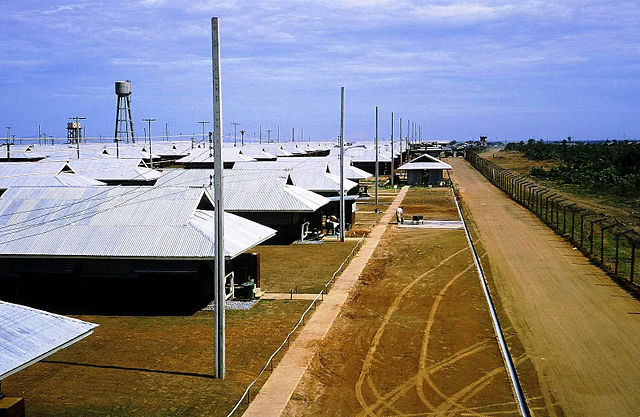

On June 20, 1968, Holm piled into the back of a C-130 cargo plane headed out of Bangkok for the 388th Tactical Fighter Wing based at Korat, 100 miles to the North.

Holm and Air Force Reserve pilot Robert John Zukowski, 23, a buddy with whom he had done all his flight training in the States, were immediately assigned a room in a hooch, a clapboard hut with eight very small bedrooms, two men to a room. The bedrooms shared a common, bug netted porch with a beat up TV and a refrigerator. The hooches were built on dirt and leaked spectacularly during daily thunderstorms.

Showers and latrines were outdoors. During one of his first showers at Korat, Holm felt a woman’s hands washing his legs. It was the hooch maid, typically an older Thai woman unofficially assigned to each hooch to clean and do laundry. “She wasn’t exactly exciting,” Holm says.

There were no sidewalks or paved roads. Nobody walked. They rode on benches in the back of dirty pickup trucks.

Dress was casual. Pilots wore unkept fatigues, flight suits, and Australian Akubra hats. They passed the time shooting geckos off hooch walls with blow guns, fashioning pyramid investment schemes, and watching Armed Forces TV. There was no basketball, baseball, ping-pong, or billiards. Drinking was the only organized recreation.

Image by Manganda333

“We did most of our drinking and took all our meals in the officer’s club. The O club would crank up at 9 or 10 at night and getting out of there was a real problem. You had to sneak out the door. And there was no telling when your roommate was getting back,” says Holm. Or his condition on arrival.

“Carrier landings” were a mainstay of squadron parties. Tables were pushed together and covered in plastic sheets. Water was sprayed on the plastic and lights flashed on and off to simulate lightening. Pilots would come in for a single ship landing on this “runway” by dashing toward it, jumping up, and sliding down the plastic on their bellies. While they were doing this they had to curl their legs to catch the arresting “wire,” a piece of rope held by two guys who raised or lowered it depending on their opinion of the pilot.

But one didn’t want to miss the rope, for at runway’s end awaited a very muddy pit holding a live, squealing pig.

Runway overshoots sent Holm and 14 others to the medical lab for stitches one night. They were sewn up without Novacaine because they had to fly in a few hours.

Parties helped relieve the stress and there was a lot of it, because 105 pilots in Southeast Asia faced lousy odds.

Public Domain

Flying 105s then was very different than the precision-guided bombing missions of today. By contemporary standards, Thuds were ill-mannered and dangerous. “To this day the only air-to-ground attack aircraft that even approaches the 105’s speed is the Russian Su-27,” says Holm.

Laden with bombs and fuel, the 105 could climb no higher than 15,000 feet. The cockpit was unpressurized. The small wings loaded up Gs and pilots would gray out or black out in tight pulls after dropping bombs.

The hydraulics, avionics and navigation systems on the 105 were unreliable. Early 105s required an average of 150 hours of ground maintenance for each flight hour. The TACAN navigation receiver would cut out when pilots dropped the landing gear. To help Thuds find targets, a Forward Air Controller (FAC) in a scout plane would hold down his microphone button and 105 pilots would key in on him using DF Reckoning, a 1930’s homing technology.

Holm frequently flew 105s in thunderstorms, through heavily defended mountainous terrain, and against an enemy that usually knew where he was going and when.

Given the 105 pilots’ appalling 75 percent survival rate, discipline within the ranks was sometimes a problem. The common retort to an unwanted order was, “What else can they do to me? Make me fly 105s in Southeast Asia?”

Image by Manganda333

This fatalism started Holm’s smoking. “Nobody thought about lung cancer. You weren’t going to live long enough to get it.” Alone in his hooch, on the third day of Holm’s smoking career he fell asleep, butt-in-hand, and burned it down. “I stopped smoking then and there.”

Holm resisted duties not related to flying. “I just flat-out refused. I was there to fly—period.” he says. “Finally, a colonel insisted that I help the flight surgeon with ‘VD Patrol.’ I was supposed to go into town and inspect the girls, and hand out color-coded stickers. White ones to safe girls and brown ones to those who weren’t.” As a member of VD Patrol, Holm got a jeep and painted the fenders pink. He would line up the girls, hand out stickers, and ask which girls wanted to work that night. “If they had a brown sticker we told them to trade with a girl with a white one.” His methods were discovered and after only a week he was relieved from VD Patrol and forced to return the jeep.

“I wasn’t much good at drinking or smoking. I failed at my one extra duty assignment. I just wanted to fly,” says Holm. Despite its shortcomings, Holm loved flying the 105. “It was very stable, a Cadillac of a fighter. It flew great in formation.”

He loved the airplane, but not the hours. Although raised on a farm, Holm disliked the 2AM wake up calls. Mission briefings often began at 3AM. Sometimes 4. There were no alarm clocks. A siren would go off when it was time to get up. Another helpful hint for the Vietcong watching us Holm thought.

Some guys would stay at the O Club too late. They would have to be dragged to briefings and actually put in their airplanes. Doped by the flight surgeon’s amphetamines and combat adrenaline, most flew well anyway.

Roscoe the dog was the briefing’s barometer. Named for Korat’s TACAN navigation fix, the adopted stray resembled a coyote. It was a bad omen if he was antsy or stood next to a pilot at the briefing. Guys Roscoe stood next to had a bad habit of not coming back. However, if Roscoe slept through the briefing usually things would be okay.

A big map tacked to the wall indicated routes and targets. Forget whizbang audio-visual, this was the Twelve O’Clock High chalkboard. Little homemade maps marked with grease pencil were the on-board navigation display.

Public Domain

Pilots tuned into certain things at the briefings, like bombing and tanker routes, and tuned out anything to do with search and rescue.

It was almost irrelevant. Bodies ejected at 600 miles an hour were mauled by friction from the oncoming air: Legs, hips, spines, and necks were snapped. If he survived, the pilot probably couldn’t walk. Where he landed was heavily defended and a “Jolly Green” rescue helicopter going in there was easy prey. When a 105 crashed it meant search and rescue was going to lose airplanes and men trying to recover a pilot who likely could not be saved.

Briefing over, pilots ate around 4 and got in their airplanes at 5.

The contents of the free bottle of booze given to a pilot the night before each mission often found its way onto the airplane.

Behind the ejection seat, 105s had a small gallon water tank connected to a hose pilots could drink through. Crew chiefs would put whatever the pilots wanted in those tanks: not just water but gin and tonics, rum and cokes, Bloody Marys, anything.

The tank was intended to provide hydration on long missions or after shutting down the air conditioner on bombing runs. The air conditioner was powered by a small ram air turbine that spun in the wind beneath the cockpit floor. If the turbine got hit by small arms fire while turning at 28,000 rpms it was like a bomb going off under a pilot’s feet. It would cripple the airplane. So pilots turned it off over threat areas. And the cockpit got hot.

After breakfast, pickup trucks shuttled pilots to the revetments sheltering their airplanes. Thuds were kept in revetments so if an airplane blew up it, the blast would not impact others parked nearby.

This thing might blow up when I start it, thought Holm.

Public Domain

Pilots could not see adjacent airplanes so starts were synchronized on the clock, rather than by using hand signals.

The 105 was started on a cart and primed with a series of simultaneously firing shotgun shells. It created giant plumes of gunpowder smoke that permeated the cockpits.

Pilots then pulled into the arming area. Crew chiefs would take the pins out of the weapons. The local chaplain would bless each flight and then walk ahead of it, holding up both hands with his index and pinky fingers extended, like the sign language symbol for peace.

Takeoffs began at 5:30 and lasted an hour.

A 105 pilot would run up his turbojet engine to full military power or 17,000 pounds of thrust, hold the brakes, put the airplane in afterburner, and push the throttle outboard. The minute he felt the fuel nozzles open up he took his feet off the brakes. Instantly the afterburner lit up and banged. Then the water injection system came on.

Loaded with 6,000 pounds of bombs, 1,200 rounds of 20mm ammunition, and fuel, the single engine 105 struggled to escape the ground.

The alcohol-water injection system generated more takeoff power by artificially increasing the density of the air going into the engine, making the air thicker as it passed through the motor and blowing more thrust out the back end. “If you didn’t get an immediate rise in exhaust gas temperature after turning on the water, you had to abort,” said Holm.

More high drama lay ahead. As a pilot lifts off precariously close to the end of the runway, he retracts the landing gear. The nose wheel swings forward, increasing drag as it folds. A knot or two of airspeed bleeds off as a result and then the airplane sinks down toward the runway. The speed brake or the tailpipe drags on the pavement. Sparks start to fly. The crew chiefs sit at the end of the runway and watch, cursing the pilot for messing up “their” airplane.

Public Domain

They were not alone. The Vietcong were there too, just beyond the fence. Shooting at Thuds with rifles. Counting airplanes and bombs. Noting the direction of flight and calling it into Hanoi. They knew where the 105s going, maybe even knew the names of targets. They knew because 105s did not have decoders on their UHF radios. It was an open channel. Anybody with a frequency analyzer could hear it and frequencies rarely changed.

Sometimes it was just too hot to get a Thud off the runway. But when a 105 launched, it was an exhilarating ride. Climb out was at 450 knots. The leading edge wing slats stayed out until 500. The wing flaps stayed down until 560. Going so fast that the nose cone on 12.5 mm rocket pods slung under the wings would sometimes fly apart, creating so much drag that the only rational option was to jettison the entire pod.

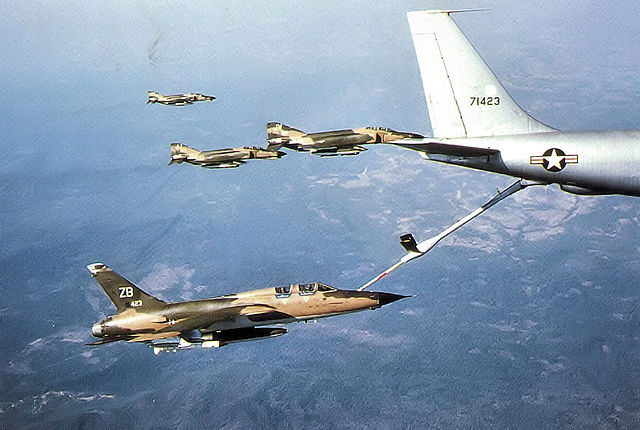

The afterburner comes off at 15,000 feet and there’s the aerial refueling tanker, a militarized version of a Boeing 707 airliner. Bad things can happen on the tanker. Occasionally a guy would “arm up,” flip a switch to remove the safeties on his bombs, while on the tanker. Distracted by refueling, he would hit the wrong switch and accidentally jettison his bombs. “You would hear an ‘oh-oh’ on the radio, look over, and see the bombs falling away,” says Holm. And no one would say a thing. Because if they did it meant a demolitions team had to go looking for those bombs.

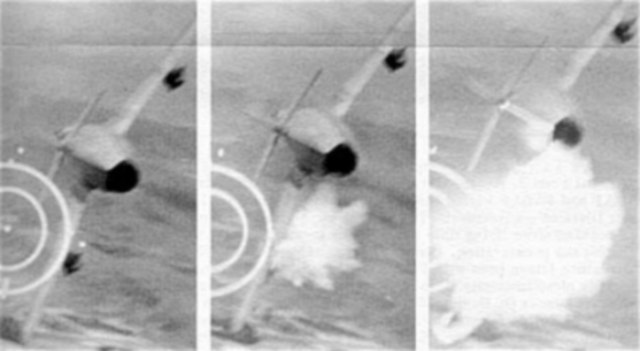

It could get worse. “One time a guy pulled up to the tanker and his whole airplane just exploded,” says Holm. “His bombs had proximity fuses and the tanker set them off.”

By the time a pilot pulls up to the tanker on that first mission, the worst of his anxiety is probably over. He may have trained in a 105 in the States but the one he picks up in Thailand is nothing like it. It is beat up and tired. On the first few missions he is getting someone else’s airplane, someone else’s crew chief. He hasn’t flown since he was in the States a month ago. He worries about getting lost in the revetments on the taxi out. Sweats about breaking off a landing gear on the caved in taxiway. It’s hot out and the plane is heavy. Will it make enough power? If he aborts takeoff late will he go off the end of the runway?

Public Domain

So now he calmly drops off the tank and flies to the FEBA, the forward edge of the battle area. “When I turned the air conditioning off and got a whiff of that country air it always seemed to calm me down a little bit,” says Holm.

Most of the time a Forward Air Controller or FAC would be waiting for the Thuds near the target in an F-100 “Misty” Fast FAC or an A-1 Skyraider, a modified World War II piston engine fighter. The FAC would mark the target with a phosphorous rocket that also alerted enemy gunners to incoming Thuds.

At this point, any remaining pilot anxiety gives way to pure confusion. “During your first ten sorties you really have no idea what you are doing,” says Holm. The triple A would come up from the ground like little sparkles. Lead will put the new guy in the #2 slot so he can keep an eye on him.

When #1 and #2 roll in on the target they were usually safe. The guys in #3 and #4 would take the hits as enemy gunners became more proficient.

Coming off the first few missions a new Thud pilot was just trying to stay with Lead. Everything is baffling and very little is remembered afterward. Holm explains, “On one of my first missions I strafed a gunner shooting at Numbers Three and Four. We bombed the target and then hit a bunch of oil drums along the road. It was a great mission and I remembered almost none of it.” So rookies don’t say much during post-mission debriefs. They don’t know where they were or what they did in great detail.

After hitting the target it’s back to the tanker and then free roaming like a wolf pack back to Korat, getting more targets from the Seventh Air Force, the FAC, or hitting targets of opportunity; checking out the roads below for suspicious activity. Two favorite targets were water buffaloes and floating junks on the South China Sea, both common ways for the North Vietnamese and Vietcong to transport war materiel.

“I really remember the boats,” says Holm. “You would roll in on them and watch the crews jump into the water right before you blew their boat away.”

Strafing trucks was trickier. Since there was no clear way to distinguish the North Vietnam-South Vietnam border from the air, a pilot had to take great care not to dispense friendly fire. Strafing enemy guns was frowned on, but everybody did it, and the loss rates from it were hellacious.

Public Domain

Then there was the satisfaction of plain old harassment. “Some guys wanted to go supersonic across North Vietnam just to break some glass,” says Holm. Part of the Thuds’ mission was simply making noise to keep the Vietcong awake as they did most of their work, running men and guns to the South, at night.

The formation would be flying low when looking for these secondary targets, using an evasive maneuver to avoid enemy fire called jinking. A flight of four would cut back and forth at overlapping intervals to protect each other. Two guys always watching the other two guys. It sort of looked like a DNA helix. One and Two were down low while Three and Four flew cover above. Everyone was always at 180 degrees from someone else.

Targets hit, there was a natural tendency to blow off steam flying back to base. Holm describes the feeling. “You just came out of a combat area. You are pretty psyched up. The adrenaline is high. The airplane is still working good. You have fuel. It’s a nice sunny day and you don’t have to shoot an (instrument) approach. Basically, the mission is over.”

And there straight out the windshield is the lovely South China Sea or a lake.

The formation rolls around the clouds. Then everybody gets down low over water, hits the afterburners, and fans out. Who is going to chicken out first? Airspeed is 500 knots and everyone is still headed down. Then someone’s 650-gallon centerline auxiliary fuel tank hits the water. He hears it. He feels it. And he grabs the stick and pulls hard. Before anyone can blink the “bouncer” has climbed 500 feet. “Once I saw a guy hit the water completely flat at 800 knots and the force just threw him back into the air,” says Holm.

Whoever hit the water got the lead and the other three ships would join up and check him over for damage. He’s OK and so everyone lands—hot. If the drag chute doesn’t pop right away the Thud is going off the end of the runway and the brakes will burn up in the process.

Pilots had to fly 100 combat missions before they could get out. Treks over Laos and Cambodia didn’t count, so most completed 140 to 150 missions before they could go home.

The most dangerous were the first ten and the last ten. “The first ten because you knew nothing,” says Holm. “And the last ten because you thought you knew everything” and became over confident. For those who made it through their first ten missions, things clicked fast.

Image by 34th Tactical Fighter Squadron Archive

Holm had only been in country a few weeks when he took out his first big target, a fjord over the Mekong. He nailed it with an AGM-20, a 2,000-pound rocket-propelled bomb. Holm fired it at a fairly flat angle because of a low cloud ceiling and the need to guide the bomb with a joystick in the plane for as much as five miles until it impacted. He had to throttle back to ensure his Thud wouldn’t overrun the bomb and drive a straight line through small arms fire and triple A all the way to target. Target destroyed, he turned around and strafed the triple A site, “Just like they told us not to.”

Holm had many memorable F-105 missions but flew his favorite on Easter Sunday 1969. “I fired an AGM through the front door of a Pagoda that was filled with enemy ammunition. Blew the roof off. Got some great pictures and sent one home to Dad. I signed it, ‘Happy Easter.’”

Holm usually flew 20 missions back-to-back and then took a few days off. For “fun,” he visited other bases and rode in bombers or FAC planes as an observer. While riding on a night mission in an A-26 Invader, one of the two engines on the World War II medium bomber caught fire. Then it suffered a complete electrical failure. Flying right seat in a small O-2 Slow FAC plane, Holm saw a 105 come apart in his windshield. The pilot ejected, but the O-2 nearly clipped him on the way down.

When he wanted a tamer diversion, Holm grabbed Zukowski and called a cabbie they knew who voluntarily sat in back while they drove like banshees down the freeway at 100 miles-per-hour to Patio Beach or Bangkok. Patio Beach looked like Tahiti. Many U.S. service personnel went there for R&R. On one trip to Bangkok, Zukowski met a South Vietnamese nurse. They got married on February 8, 1969. Three days later he was lost over Laos.

“To this day, I don’t remember if I made any friends in Thailand other than Zukowski,” says Holm. “Part of it was that after he got shot down I didn’t care if I knew any of them anymore.”

Holm says he didn’t think about it much at the time, he just focused on flying his airplane. “I had more loyalty to the airplane than to the people in the squadron. You gotta pick something to trust in combat. I couldn’t trust that people would still be there. So I trusted that the airplane would always work. And it did.”

The squadron threw him a nice party when he had his official “100” combat missions. As he taxied in they greeted Holm with a procession. All those pickup trucks with benches in the back. Fire engines. Government vehicles. Basically anything with wheels on it. There were sirens and American flags and Roscoe the dog. They blew off canisters of smoke grenades and fire extinguishers. They walked Holm from the airplane and soaked him with water balloons and a fire hose.

The Air Force began pulling F-105s out of Vietnam in 1969. Air Force Reserve and Air National Guard units flew surviving aircraft until 1984. While several are in museums, not a single F-105 remains in flying condition today.

Major Robert Zukowski’s remains were recovered in 1996. He is buried in Resurrection Cemetery in Justice, Ill., just south of Chicago. A few years ago Holm went to Washington and found his friend’s name on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Panel 32W, Row 18.

Time and emotional self-defense have blotted some of Skip Holm’s F-105 experience from memory. He still remembers flying low and fast and loving it.

- Hungary Defies The Globalist War Machine: “Hungary Will Not Succumb To EU Blackmail”

- Slovakia Vows To Veto Ukraine’s Admission To NATO

- Romania’s Corrupt Government Has Become An Arm Of The Democrat Party In The U.S.

As a 100 mission NVN F-105 pilot who flew from Korat, Feb-Aug 1967, had flown the Thud in Europe beforehand, and instructed at McConnell in F-105s from 67-69, I find much of what Huber recounted accurate and engaging, but some specifics were inaccurate or overstatements. Suggest reading with that in mind--doesn't detract from the main message--great airplane, tough mission. I, too, loved flying the Thud, first love--also flew the F-4 & F-16, both fine airplanes, especially the F-16.

This is the largest embellishment, failure of fact, hyperbole, and collection of b.s. I have read since the fanciful Flying Through Midnight (C-123.) I have sent my critique to the publisher. If you want a copy, write me and I'll fwd to you. JFP 102 msns F-105

I'm also not a fan of gross exaggerations, so I'd be interested in your (and other) opinions.

I'm not a total rube (BienHoa - 1968-69 / Udorn - 1971-72)