Guest post by John Huffman

Mighty Men Herald – October of 2023

On November 14, 1938 an important meeting was called in the Cabinet Room of the White House. Twenty years earlier, almost to the very day, the Great War had come to a close. Now the world was on the verge of war again. And the United States was dangerously unprepared.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt had assembled several important members of his cabinet along with officials from the War Department to discuss a proposition to dramatically increase production of military aircraft for a coming conflict. It was Roosevelt’s hope that sending warplanes to Great Britain could help the war effort without committing the United States to another global war.

With a standing peacetime army of 174,000 officers and soldiers, the military power of the United States ranked 18th in the world. Meanwhile, Germany was flexing its imposing muscles in Europe. On the other side of the world, the Japanese Empire was slowly extending the tentacles of its growing navy into the vast expanses of the Pacific.

Few men understood the overwhelming nature of the threats. When President Roosevelt was wheeled into the Cabinet Room to begin the meeting, he explained to the assembled military officers and War Department officials the need for the United States to increase production of warplanes at a budget of $500 million dollars.

One by one, the generals and statesmen around the room gave their approval of the President’s plan. After being elected to office three times, President Roosevelt was used to things going his way. Everyone in the room expressed their assent to the plan.

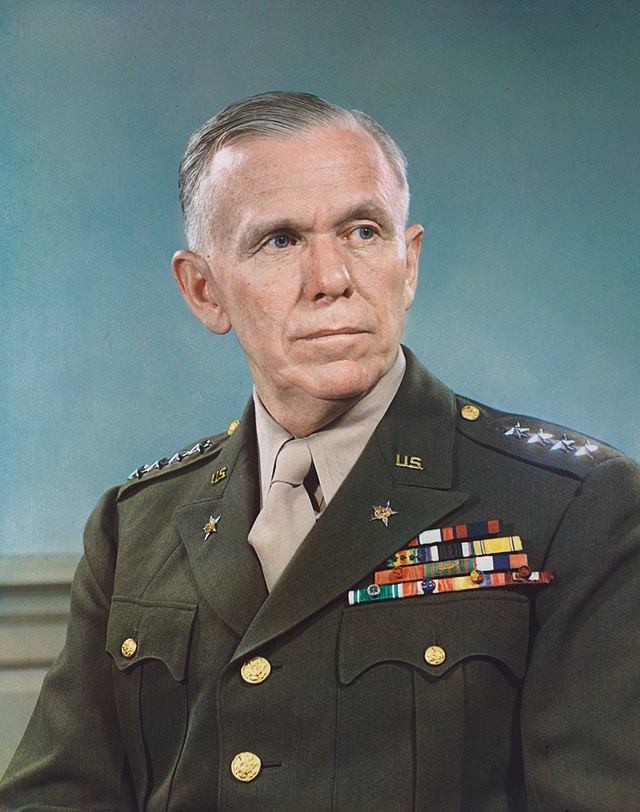

Finally, President Roosevelt turned to Brigadier General George Catlett Marshall. The President addressed Marshall by his first name, “Don’t you think so, George?”

General Marshall answered respectfully but firmly, “I am sorry, Mr. President, but I don’t agree with that at all.” Though no man realized it, Marshall was thinking on a far grander scale than any other man in the room. Without asking for an explanation, President Roosevelt adjourned the meeting. Some of his friends thought that General Marshall had ruined his career.

Many years earlier, as a young staff officer, he had dared to speak frankly to General John Pershing, the Supreme Commander of the American Expeditionary Force in Europe. Now, he was not afraid to speak the truth again.

Marshall feared that throwing American money and effort into airplanes alone was unsound policy. Five hundred million dollars and five thousand airplanes was not enough to avert the threatening storm.

Over the coming months, various proposals were drawn up and discussed among the leaders at the War Department and the Cabinet. Marshall continued to urge for a rapid buildup of men, munitions, manufacturing, transportation, training, logistics, and air and naval power.

On April 23, 1939, Marshall was summoned to the Oval Office. It was a Sunday afternoon. Roosevelt was wearing a sweater and working on his stamp collection. The President got right to the point. “General Marshall, I have it in mind to choose you as the next Chief of Staff of the United States Army. What do you think about that?”

Marshall looked the president right in the eye. “Nothing, except to remind you that I have the habit of saying exactly what I think . . . Is that alright?” Roosevelt responded with one word. “Yes.”

Marshall wanted to make sure the President took his words seriously. “You said yes pleasantly, but it may be unpleasant.” General Marshall then stood, adding, “I feel deeply honored sir, and I will give you the best that I have.”

After a long career already of thirty-seven years in the army, staff work had relegated Marshall to a modest rank of Brigadier General. Now, in a moment, he was to become a four-star commander, tasked with equipping, training, and leading the United States into war. In the early morning hours before his appointment, forty two divisions of armor and infantry, supported by the Luftwaffe, invaded Poland in an overwhelming show of force.

Two days after his swearing in, Britain and France declared war against Germany. Marshall grimly faced the reality. America was not prepared for war. Germany had roughly one hundred infantry divisions. The United States could field four infantry divisions at best.

In the short span of only three years from 1939 to 1942, General George Marshall had transformed the United States Army. He had increased its power forty-fold into a military machine of 8 million soldiers. By force of his own personal leadership, he had demonstrated conclusively that the war could only be won by dealing a death blow to the Axis

Marshall had an instinctive ability to see potential in other officers. For years, he had kept a “little black book” full of notes on the various merits of other officers. Now, he pulled out that little notebook and selected the commanders that would become famous in the annals of military history, Omar Bradley, Dwight D. Eisenhower, and many others. Marshall had the unique ability and humility to support and recommend other commanders with whom he had clashed in the past, men such as Douglas MacArthur.

Marshall always lived up to his reputation of speaking truth, even when it hurt. He disappointed both Roosevelt and Winston Churchill on several occasions because he told them what was true rather than what they wanted to hear.

By the time his long-cherished invasion of Europe was ready to move from the planning stage to active operations, it was widely expected that George Marshall would take personal command of the invasion. Most historians agree that General Marshall wanted the active field command, but instead of resenting the appointment of Eisenhower, Marshall personally preserved the handwritten order to present it to Eisenhower. Roosevelt paid Marshall a high honor when he explained that he could not sleep without Marshall at his side. From his office in Virginia, George Marshall orchestrated the war on two vast fronts.

When victory finally came, Marshall’s service to his country was not over. He understood, perhaps more than any man in the world, what it would take to rebuild Europe and the devastated Pacific. He saw the rise of Soviet Power in Asia as a dangerous threat, and took decisive steps to advance the cause of freedom around the world.

As Secretary of State under Truman, General Marshall commanded the respect of men on both sides of the political spectrum. Truman insisted that the plan to reshape Europe be called “The Marshall Plan” because the president knew that the world had a deep respect for the integrity and selfless spirit of General Marshall. His retirement plans were interrupted by another war in Korea, and General Marshall was asked to become Secretary of Defense.

The General’s personal life matched his public life. A graduate of the Virginia Military Institute in Lexington, Virginia, he was a man of simplicity, integrity, and humility. He loved riding his horse in the early morning along the banks of the Potomac River.

He was a devoted husband to his first wife, Lily, who died of complications after thyroid surgery. His second wife, Katherine, a widow with three children, was a lifelong companion to the General and he loved her truly and faithfully. The General had no children of his own, but he dearly loved all children and he took under his care the children of Katherine.

Perhaps his greatest moment came when, during a busy high-level staff meeting, a young soldier accidentally entered the room. While the others glared at the interruption, General Marshall kindly got up and redirected the intruder to the room he was seeking.

After fifty years of continuous public service, George Marshall retired to his quiet home, Dodona Manor, in Leesburg, Virginia. He raised vegetables in his garden and only came out of retirement to attend the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953. When he entered Westminster Abbey to take his seat, there was a stir of commotion as the congregation rose. Marshall looked around to see what dignitary had entered behind him, and then it dawned upon him that everyone had risen out of respect for him.

Marshall was afflicted by a series of strokes that eventually brought him to Walter Reed Hospital. An eighty-four-year-old Winston Churchill came to visit, standing silently before the General. Churchill said not a word, but wept in the presence of Marshall.

General Marshall was a modest and sincere Christian gentleman. He eschewed the pomp of personal grandeur and display, and requested that he be laid to rest at Arlington in a simple funeral service. He had kept his promise to “give his best” to his country, and his example of courageous leadership continues to inspire each generation.

Drawn from: George Marshall by David L. Roll and 15 Stars by Stanley Wientraub

Portrait of Marshall provided by the George C. Marshall Foundation www.marshallfoundation.org

With deep appreciation for:

Andy Williams, a graduate of VMI and a personal friend who first encouraged me to study General Marshall

David Hein, who has written several helpful and insightful articles on the faith and character of General Marshall

Melissa Davis, the librarian of the George C. Marshall Foundation, who offered valuable advice and direction

I am appreciative to the author of this article for putting this together. The example of integrity exemplified by General Marshall is a lesson in wise living that is not taught enough today, in my opinion.

Thank you for enriching my day.

Amazing article about an amazing man- I will be sharing his story with many- If I were a Cadet, this is the kind of Officer I would aspire to be.